Weekly Briefing, Vol. 29. No. 4 (EE) May 2020

A ‘Baltic Bubble’ and experiences of the UN SC rotating presidency

There is a strong terminological cliché existing in the field of international relations – many scholars and practitioners visibly enjoy generalising on the Baltic states, quasi-unifying Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania into the geo-strategic as well politico-economic one. Quite often, such generalisations are made for no reason, in a ‘by the way manner’. In reality, these countries are uniquely different, and there is a high number of serious studies that evidently prove that particular point. However, it does not deny the trio’s ability to quickly establish an unbreakable bond of regional solidarity to challenge any crisis (together) and come out from any tough times (also together). Even though each of the Baltics chose its own way to tackle the pandemic, the conversation had always been on, and the plans on recovery had been discussed to make it in a seamless fashion.

As a result, from 15 May, the Baltic states decided to open their internal borders restoring free movement within the countries for residents of the trio. In an ERR-issued summary, the decision was featured by the following elements: 1) free movement is restored for “residents of Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia and for people staying there legally” (it applies to citizens or those who have permanent residency or a residence permit); 2) a 14-day quarantine period will not apply when crossing a border; 3) people can only travel if they show no symptoms of COVID-19; 4) a person must not have left the country they are coming from in the previous 14 days; 5) a person arriving from a third country – outside of the so-called Baltic ‘bubble’ – must abide by the previous rules and isolate herself/himself for 14 days before she/he can travel to another Baltic state[1].

In a way, Estonia, together with its Baltic neighbours, had a compelling reason to favour the establishment of the ‘Baltic bubble’ – all three nations have rather high level of testing, and the numbers of diagnosed cases of the COVID-19 did not seem to be out of control. As of 15 May, for example, Estonia (the smallest of the three) had 1,766 diagnosed cases of the virus with 63 deaths; in Latvia (with its population being a bit less than 2 million), there were 970 cases and less than 20 people died because of the COVID-19; the situation in Lithuania (about 3 million inhabitants) was somewhat similar with 1,523 diagnosed cases and 54 deaths (please see Table 1 for more details)[2].

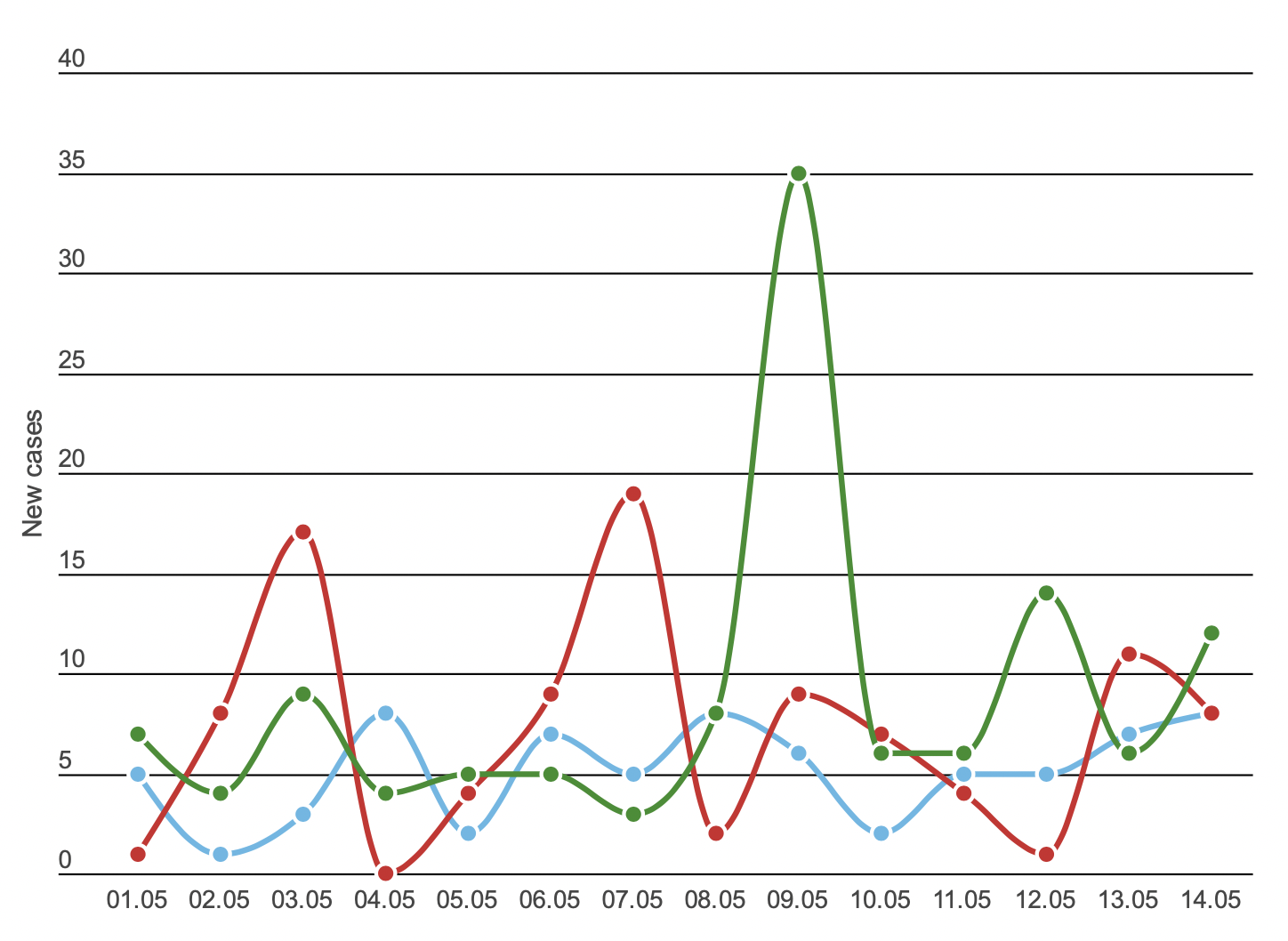

Table 1: New COVID-19 cases by day for Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania: 1-14 May 2020

Estonia: blue / Latvia: red / Lithuania: green

Source: Summaries by ERR[3]

On the broadest international stage, in May, Estonia held the country’s first ever presidency of the UN Security Council. On such a super-special occasion, Estonia took a chance to announce the following priorities, which the country’s actions are to be guided by, considering its new status. The Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs specified that Estonia, firstly, “will keep the coronavirus crisis in focus, as the crisis also poses a threat to the global security environment”[4]. Secondly, the country will be pushing transparency and working methods’ improvement during the pandemic, trying to ensure that “transparency and efficiency of the Council’s work are safeguarded to the maximum extent”[5]. Thirdly, Estonia will be underlining that “[p]rinciples of international law must be followed and violations should be highlighted”, including “the prohibition of the use and threat of force”[6]. Fourthly and finally, the Estonian presidency of the UN Security Council will be featured by raising “the issue of emerging security threats”, since “cyberattacks and cybercrime have increased during the pandemic”[7].

In accordance with the aforementioned set of priorities, on 22 May, Estonia arranged its signature event of the UN Security Council’s Presidency, ‘Cyber Stability, Conflict Prevention and Capacity Building’. The idea of the meeting was to sharpen the international community’s focus conflict prevention in order to ensure “a stable and peaceful cyberspace”[8]. Personalities wise, the event was opened by Jüri Ratas, Estonian Prime Minister, while their briefs delivered Izumi Nakamitsu, High Representative for Disarmament, David Koh, Chief Executive of the Cyber Security Agency of Singapore, and James Lewis, Director for Technology Policy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies[9]. Considering the Estonian side’s nearly unmatched experience in dealing with cyber threats (after all, it was Estonia that, in 2007, “faced cyber-attacks that have been widely acknowledged as the world’s first cyber war”[10]), it was logical to arrange a high-level meeting that, as declared, “allowed states to share their experiences on the application of international law and cyber norms in cyberspace, on which regional cooperation formats have been successful in ensuring cyber stability, and on identifying shortcomings in dealing with cyber threats”[11]. Back in time, a massive cyber attack from Russia literally transformed Estonia[12] and its vision on cyber security. Most probably, the country’s temporary but very direct participation in the UN Security Council’s activities can assist it in delivering a highly important message on the international system’s most ubiquitous domain, cyber space. Arguably, depending on the world’s decision, it can become either a strong unifying platform or a field to accommodate non-compatible approaches.

In the meantime, there is a noticeable attempt made by many countries to utilise the experiences of dealing with the pandemic on the way to ensure a more effective as well as internationalised response to future crises of similar types. In such a context, there are multiple calls coming from all corners of the world – not necessarily orchestrated or arranged by particular world powers – on formalisation the process to reform the World Health Organisation/WHO that, arguably, did not/is not perform/ing well during the latest crisis. In March 2019, The Lancet (via its globally-read editorial) noted a certain cognitive discrepancy between Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus’ inaugural speech (“I do not believe in perpetual reform and I think WHO staff are reformed out”) and the fact of unveiling “the result of a 20-month-long consultation for reform”[13], which followed later on. In any case, “the most wide-ranging reforms in the organisation’s history”[14] are yet to be accomplished, if they have even been commenced at all. From the Estonian point of view, the country’s position is that “there is no alternative to the WHO in terms of international cooperation”, and, therefore, “it is vital for the organisation to remain active”[15]. However, as the country’s Minister of Foreign Affairs argued, “the WHO was not effective in its efforts to stop the virus spreading in the world during the coronavirus crisis”[16]. In addition, Minister Reinsalu noted that

Estonia also wants the WHO reformed, an independent investigation to get to the bottom of problems. Whether the organisation can be reformed right now, while the virus is still spreading and the crisis still with us is another matter. We need to be able to solve more acute problems first.[17]

Most probably, during the Estonia’s partaking in the UN Security Council, the WHO-associated issues will be brought up perpetually. There is an obvious practical need to digitalise the exchange of health data between countries, and this necessity was underlined by Prime Minister Ratas in his conversation with the WHO’s Director-General:

[Estonian] experts started working with colleagues from WHO half a year ago to find the best ways to use Estonian e-experience and distributed system architecture. We are ready to help the WHO to connect health information systems and databases and ensure their interoperability through the involvement of both the Estonian and Finnish private sectors. Better and safer data exchange between countries creates the prerequisites for much greater global cooperation and trust.[18]

A small country helping out a nearly dysfunctional international system? Why not? It is much better than doing nothing or pretending that everything is just fine when it is definitely not the case.

[1] ‘‘Baltic Bubble’: Rules for traveling from Estonia to Latvia and Lithuania’ in ERR, 15 May 2020. Available from [https://news.err.ee/1090243/baltic-bubble-rules-for-traveling-from-estonia-to-latvia-and-lithuania].

[2] ‘‘Baltic Bubble’: Rules for traveling from Estonia to Latvia and Lithuania’.

[3] ERR. Available from [https://news.err.ee/1090243/baltic-bubble-rules-for-traveling-from-estonia-to-latvia-and-lithuania’.

[4] ‘Estonia’s presidency in UN Security Council’ in Välisministeerium. Available from [https://vm.ee/en/activities-objectives/estonia-united-nations/estonias-presidency-un-security-council].

[5] ‘Estonia’s presidency in UN Security Council’.

[6] ‘Estonia’s presidency in UN Security Council’.

[7] ‘Estonia’s presidency in UN Security Council’.

[8] ‘Signature Event of Estonia’s UNSC Presidency: Cyber Stability, Conflict Prevention and Capacity Building’ in Välisministeerium. Available from [https://vm.ee/en/activities-objectives/estonia-united-nations/signature-event-estonias-unsc-presidency-cyber].

[9] ‘Signature Event of Estonia’s UNSC Presidency: Cyber Stability, Conflict Prevention and Capacity Building’.

[10] ‘How Estonia became a global heavyweight in cyber security’ in EAS, June 2017. Available from [https://e-estonia.com/how-estonia-became-a-global-heavyweight-in-cyber-security/].

[11] ‘Signature Event of Estonia’s UNSC Presidency: Cyber Stability, Conflict Prevention and Capacity Building’.

[12] Damien McGuinness, ‘How a cyber attack transformed Estonia’ in BBC, 27 April 2017. Available from [https://www.bbc.com/news/39655415].

[13] ‘WHO reform continues to confuse’ in The Lancet, Editorial, vol. 393, issue 10176, P10176, 16 March 2019. Available from [https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(19)30571-9/fulltext].

[14] ‘WHO reform continues to confuse’.

[15] ‘Reinsalu: WHO needs reform’ in ERR, 31 May 2020. Available from [https://news.err.ee/1096613/reinsalu-who-needs-reform].

[16] Urmas Reinsalu in ‘Reinsalu: WHO needs reform’.

[17] Reinsalu.

[18] Jüri Ratas in ‘Ratas: We want to work with WHO to digitalize exchange of health data’, ERR, 13 May 2020. Available from [https://news.err.ee/1089290/ratas-we-want-to-work-with-who-to-digitalize-exchange-of-health-data].