Weekly Briefing, Vol. 67. No. 4 (RO) November 2023

Strategic, Special or Extended. Short Introduction to Romanian Foreign Policy

Introduction

The examination of Romanian foreign policy during the period following the end of the Cold War has garnered significant attention from both academic and practical perspectives. In the wake of the Cold War, Romania encountered the challenge of adjusting to changing global dynamics while simultaneously ensuring the preservation of its national sovereignty. Scholars and practitioners have conducted research and analysis on the development of Romanian foreign policy, placing particular emphasis on significant phases such as the era of Euro-Atlantic integration spanning from 1994 to 2007. Romania’s unwavering commitment to national security is exemplified by its steadfast efforts to cultivate and sustain robust diplomatic relations with prominent global powers, notably through its active engagement with NATO and the EU.

As such, this briefing delves into Romania’s foreign policy commitments as manifested through its Strategic, Special, and Extended Partnerships. The aforementioned collaborations, which have been meticulously established with nations spanning the Americas, Asia, and Europe, serve to highlight Romania’s strategic fortitude and its commitment to engage in today’s global affairs. In other words, this briefing aims to provide a comprehensive description of the several types of partnerships that Romania engages in diplomatically, namely Strategic, Special, and Extended Partnerships.

Empirical descriptions and developments

Scholars and practitioners have long been interested in the issue of conceptualizing Romanian foreign policy, especially as global affairs have become more complex either after the Cold War, after the end of the Cold War, or in a post-Cold War order, as Marius Ghincea suggests[1]. In this regard, it is important, for the first part of this briefing, to bring forward some ideas regarding the evolution of conceptualized Romanian foreign policy after 1989 in order to understand how Strategic, Special and Extended Partnerships evolved and why these are relevant in today’s Romanian foreign policy.

To begin with, Florin Abraham offers an interesting overall assessment concerning the evolution per se of Romanian foreign policy. He believes that “the peaceful end of the Cold War” generated significant transformations in global affairs, resulting in the fact that Romanian leadership “sought to understand and anticipate” these end-of-the-Cold War transformations[2]. As such, the main principle of Romanian diplomacy was driven by the necessity to adapt to those evolving circumstances in order to safeguard the integrity of the Romanian state. In supporting these assertions, Florin Abraham induces the idea that the integrity of the Romanian state had experienced various sequences, and “the success in establishing the modern Romanian state (1859-60), winning independence (1877-8) and creating Greater Romania (1918-20), but also the losses of territories and population in 1940, have created among diplomats, the military, and statesmen an ethos of sacrifice for the defense of state borders”[3].

Romanian elites maintain that the effectiveness of the country’s boundaries is determined not only by demographic factors, economic strength, and national policies but also by the interplay of interests and rivalries among the major global powers[4]. Maintaining strong diplomatic ties with at least one major global power and ensuring the security of national borders have been longstanding strategic goals since the “mid-nineteenth century to the present day”[5]. The principal thread of continuity in Romania’s foreign policy remains steadfast, irrespective of the various political governments that have succeeded one another. Following the year 1990, participation in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Union (EU) came to be regarded as the most reliable means of safeguarding national security and maintaining border integrity, according to Florin Abraham[6].

Moreover, the mobilization of large domestic resources, the relinquishment of qualities of national sovereignty, and the population’s stoic acceptance of substantial social sacrifices were undertaken in order to attain Euro-Atlantic integration[7]. These measures were perceived as necessary costs to safeguard national security in Romania, thus establishing an international policy on a strong basis of widespread endorsement for key objectives[8]. In line with these, the same Florin Abraham believes that at least two stages regarding Romania’s international policy could be described:

- The incertitude stage (1989-1993), in which “Romanian diplomacy exhibited prudence towards the USSR and the Russian Federation”, nonetheless being “conscious that its future lay in the West”, and ultimately emerging “from international isolation” in 1993[9];

- The Euro-Atlantic integration stage (1994-2007), in which “the major preoccupation of Romanian diplomacy was accession to Euro-Atlantic institutions”[10].

Florin Abraham’s two stages contribute to the comprehension of several aspects relevant to and for this briefing, as well as the suggested overall perspective on the empirical evolution of Romanian foreign policy. First, it highlights an omnipresent idea that has given meaning to other subsequent debates and contributions that have come into being because it positions, conceptually and normatively, the beginning of conceptualized Romanian foreign policy. Second, it rightly argues that “after EU accession, the main objective of Romania’s international policy was the creation of a credible country profile…”[11] which, in turn, marked the beginning of a new set or stage in analyzing the dimension of conceptualized Romanian foreign policy, post-Euro-Atlantic integration. As a result, Marius Ghincea, referring to some premises of Romanian foreign policy in a post-Euro-Atlantic integration context, argues that “Romania’s strategic documents and public debates on salient foreign policy issues indicate a prevalence of a particular symbolic schema”[12]. Thus, departing from the belief that “multilateral cooperation has not completely given way to zero-sum world politics, despite the pervasiveness of competitive logic in large areas of international politics”[13], Marius Ghincea points out the fact that Romanian foreign policy exhibits a consistent and dependable approach in a post-Euro-Atlantic integration context, characterized by its ability to offer proficient knowledge in specialized domains and on matters pertaining to its immediate concerns[14]. In addition, he acknowledges that Romania has demonstrated itself as a proficient and steadfast collaborator with its Western partners while also serving as a steadfast proponent of a rules-based international order, the consensus among Romanian elites and the general public demonstrating significant success over the course of the last three decades[15]. However, Marius Ghincea continues, “faced with Russia’s increased assertiveness, Bucharest seems to operate on the basis of a hawkish logic that any military vulnerability should primarily be remedied by military means. This leads to a high degree of overlap between the foreign policy and defense policy of the country, [yet] faced with the increasing assertiveness of Russia in the Black Sea region, this is both legitimate and understandable”[16].

By addressing the issue of conceptualizing Romanian foreign policy, it is important to scrutinize the origin of this approach identified previously by scholars and practitioners and to acknowledge indeed that this could “originate either in the Cold War strategic thinking that was perpetuated after 1989 or in the post-Cold War period dominated by the U.S.’s unipolar moment that shaped Romanian strategic culture. [Afterall] Romania’s foreign policy actors still interpret the world according to a cognitive template of the past”[17]. Therefore, Romania’s “preoccupation for defense issues affects the breadth and depth of its foreign policy, limiting Romania’s ability to engage in substantive terms on a larger and more varied number of global and regional issues”[18]. In this regard, Marius Ghincea suggests a framework which consists of a collection of assumptions – this symbolic schema that has previously been mentioned –, ideas, and predispositions that influence the manner in which the country’s elites and the general public perceive global politics and Romania’s position within international politics[19]. This symbolic schema serves as a foundation for the foreign policy consensus within Romania and, through influencing the perspectives of both the elites and the general public, establishes the parameters within which actions and beliefs on global affairs are deemed feasible and appropriate. Marius Ghincea, in this line with this thought, believes that the process also determines the inclinations of states, commonly known as the national interest, and significantly impacts the conduct of foreign policy, with the primary objective being to delineate the principal components of this symbolic schema, without necessarily aiming to critique their existence.

According to the same analysis, Iulia Joja “persuasively” suggested that the origin of this symbolic schema can be traced back to the prevailing strategic culture, which has undergone changes throughout time[20]. This culture has been influenced by individuals who strategically utilize historical memory to serve their own objectives. Iulia Joja’s cited study and Marius Ghincea’s subsequent analysis provide evidence for the aforementioned evaluation, while both presenting a counterargument to the prevailing narrative regarding the causative variables that influence Romanian foreign policy. The prevailing narrative, rooted in historical determinism, is called into question, in contrast to the prevailing views of many practitioners and certain analysts. In this regard, Marius Ghincea argues that historical memory exerts a relatively constrained influence on the formation of foreign policy, making it imperative that scholars and practitioners refrain from succumbing to a simplistic and narrow-minded philosophy of history[21]. The significance of history becomes devoid of meaning in the absence of political and social interpretation because political elites engage in the construction of historical narratives as a means to justify, validate, and give significance and consistency to their present policy preferences. Historical determinism might be seen, as highlighted by Marius Ghincea, as a limited analytical framework with limited explanatory capacity, an alternative explanation is that political elites, who have predetermined their desired course of action, strategically employ historical narratives to justify and strengthen their policy decisions, thus presenting them as rational and unavoidable[22].

With respect to this matter, Marius Ghincea persists in explaining the taxonomy of this symbolic schema, describing it through “three broad categories”[23]. The first category includes “key assumptions and notions” pertaining to the nature of international relations and global politics. These fundamental notions offer valuable frameworks for understanding the nature of the world, hence influencing the development of a comprehensive perspective commonly referred to as a worldview[24]. The second category encompasses beliefs and conceptualizations pertaining to Romania’s participation in global politics, which shape its foreign policy identity and role conception, while the third category encompasses notions and inclinations on Romania’s aspirations and objectives in international relations, establishing the parameters for determining suitable priorities and preferences in global affairs[25].

Finally, Marius Ghincea’s primary contention posited within his analysis is that the symbolic schema employed yields both advantages and disadvantages for Romanian foreign policy. Given the ongoing global transitions and their ontologies, his objective is to propose targeted strategies to limit the potential increase in costs resulting from this symbolic schema. In certain aspects, the symbolic schema may have proven inadequate and necessitated a revision. This is particularly apparent when considering the fact that Romania maintains strained diplomatic relations with a number of neighboring nations, as well as some partners within NATO and the EU, in Marius Ghincea’s view, when discussing the issue of promoting “a Western security agenda through the tactic of securitization”[26]. The aforementioned symbolic schema, which is posited to merit ongoing continuation, has been observed to impede the further development of strategic alliances with prominent European nations, as the same Marius Ghincea points out, namely France and Germany[27].

Some ideas on Romania’s Strategic, Special and Extended Partnerships

According to the Presidential Administration, “Strategic Partnerships and special relations with other states… will [also] be further strengthened in order to increase our country’s [Romania] strategic resilience”[28]. In other words, the specialized literature asserts that “Romanian foreign policy rests on the premise that the Western core will remain united and unscathed in the face of increasing challenges from outside the West, [despite the fact that] growing tensions between the two sides of the Atlantic are putting into question some of Romania’s key assumptions about the indivisibility of the West”[29]. Nonetheless, it has been noted that “a series of remarkable changes in Romania’s strategic discourse over 25 years”[30] have been observed by scholars and practitioners alike.

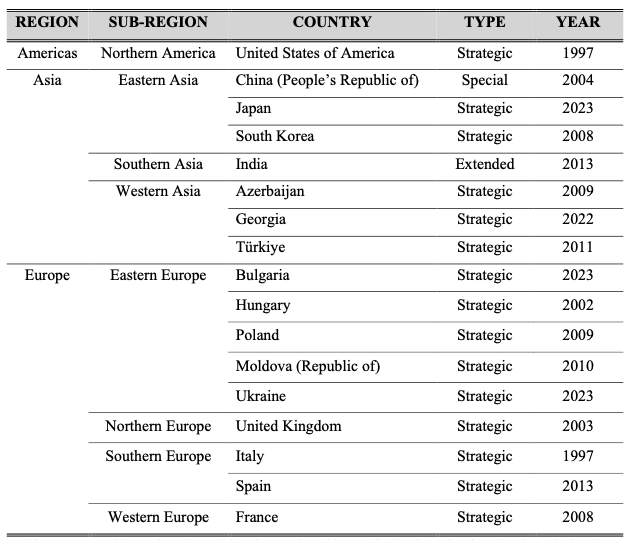

The reorientation of Romania’s foreign and security policy from a state of uncertainty in the early 1990s to a strong alignment with Western values has resulted in a reinvention of national identity in relation to security comprehension and strategic analysis. The discourse around Bucharest’s position in the region and within Europe underwent a transformation, shifting from an isolationist and self-reliant strategic mindset to one that emphasized integration, shared values, and collaborative action in the realm of security[31]. In this regard, a “series of bilateral relations are distinguished by solidity and scope”[32]. And indeed, “from this perspective, the development of Strategic Partnerships and other bilateral relations, the promotion of the strategic relevance of the Black Sea, the projection of Romania’s profile as a factor of stability and promotion of EU values in the region, as well as the support of political, economic and security interests in areas of interest” are part of Romania’s “concrete benchmarks” of foreign policy[33]. As a consequence, Table 1 below displays the countries with which Romania has developed Strategic, Special and Extended Partnerships.

Table 1. Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Romania. Table complied by the author, based on the United Nations geoscheme.

For example, during a joint conference held on 22 July 2013 in Madrid, the Prime Minister of Romania and the Spanish Prime Minister made a political announcement on the establishment of a Strategic Partnership between the two nations. The Romanian-Spanish Strategic Partnership aims to enhance the bilateral relations between the two countries, with a particular focus on important areas such as infrastructure, energy, European politics, internal affairs, and agriculture. The Strategic Romanian-Spanish Partnership, according to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Romania[34], entails ongoing consultations through a structure of joint intergovernmental meetings, characterized by a pragmatic and adaptable format. The inaugural meeting between the Governments of Romania and the Kingdom of Spain took place on 23 November 2022, in Castellón de la Plana, the two sides issuing a Declaration of the Inaugural Joint Government Meeting which signifies the profound cooperation between Romania and the Kingdom of Spain, and enhances collaboration in the bilateral, European, and Euro-Atlantic spheres. Therefore, the objective of the Romanian-Spanish Strategic Partnership is accomplished by the augmentation of discussion at various levels, the promotion of economic, social, and cultural exchanges, and the enhancement of sectoral collaboration[35].

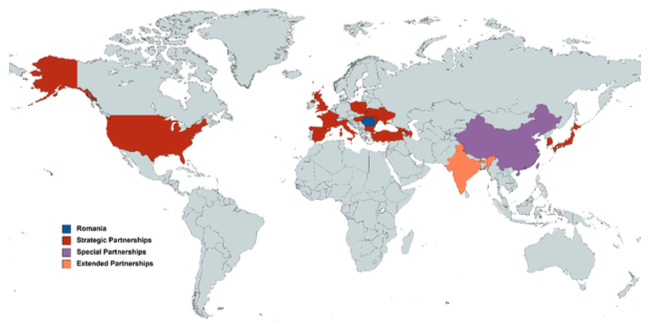

Source: Map created by the author, based on Table 1.

However, in this second part of the briefing, what remains evident to clarify is the distinction between Strategic, Special and Extended partnerships. As a result, the aforementioned contention can be subject to debate. The Strategic Partnerships of Romania, as indicated by Table 1, signify the most significant level of bilateral relations and collaboration between Romania and the respective countries. Strategic Partnerships primarily involve countries from Europe or neighboring regions, such as the South Caucasus, with the aim of integrating and accomplishing certain objectives. In spite of this, the purpose of these Partnerships has been extended over time. The Strategic Partnership established with Azerbaijan seeks to enhance the political dialogue between the two nations, with a specific emphasis on fostering collaboration in the field of energy[36]. The collaborations with Italy and the United Kingdom have highlighted the focus on European affairs, particularly in the context of the Romanian-British Strategic Partnership’s cooperative endeavors before Brexit[37]. Various other Strategic Partnerships, including the one established with France, aimed to enhance bilateral and multilateral collaboration with the goal of furthering European integration[38]. The Strategic Partnerships with the Republic of Moldova or Georgia are also significant in terms of advancing European integration, given the strategic objective of the two to join Euro-Atlantic institutions[39]. Having said this, it can be inferred with relative ease that all of Romania’s Strategic Partnerships have a distinct cooperative or co-operation element, aligning with Iulia Joja’s perspective on a “new paradigm of Romanian foreign and security policy”, as she articulates the fact that “older strategic concerns and regional preoccupations have rebounded, while simultaneously new elements have come to light…”[40]

A second tier of Partnerships is represented by Special Relations. In this category, Romania classifies its relations with China on the basis of Special Relations, Georgia having previously been in this category before elevating the Partnership with Romania to a Strategic one. According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Romania[41], diplomatic relations between Romania and China are characterized by a mutual political agreement, which was officially endorsed by the respective Romanian and Chinese Presidents during Hu Jintao’s visit to Romania in 2004[42]. As such, Hu Jintao’s visit to Romania marked the signing of the Joint Declaration by the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of Romania on Establishing a Comprehensive Friendly Cooperative Partnership[43] which paved the way for a continuous facilitation of bilateral exchanges and cooperation programs, thus elevating Romania’s relations with China to the level of a Special Partnership.

Subsequently, the third and last tier of Partnerships in Romanian foreign policy are those represented by Extended Partnerships. Similar to the second tier, this third tier encompasses one Partnership, namely the Romanian-Indian Extended Partnership, agreed by the foreign ministers of the two countries in New Delhi on 8 March 2013[44]. This Extended Partnership, according to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Romania, provides the basis of a “consolidated cooperation” between Romania and India, in a variety of sectors, such as defense, space, economy and trade or infrastructure, nuclear energy for civil purposes, oil and natural gas exploitation[45].

Conclusion

In essence, the assessment of Romanian foreign policy, as described in this briefing, demonstrates a proactive and calculated approach influenced by historical circumstances and present-day complexities of both national interests and strategies as well as global affairs – be those affairs projected at subregional, regional, European or global level. The theoretical investigations conducted by Florin Abraham and Marius Ghincea, to name a few, reveal clarity on the nuanced development of Romanian foreign policy following the end-of-the-Cold War. Romania has demonstrated unwavering dedication to preserving its national security and border integrity, starting from the very beginnings of its the post-1989 era and continuing with a later emphasis on Euro-Atlantic integration. For example, Marius Ghincea’s analysis of the symbolic schema highlights the precise connections between historical memory and strategic culture in influencing Romania’s foreign policy stance today.

Furthermore, the cultivation of Strategic, Special, and Extended Partnerships with other states across the Americas, Asia, and Europe has emerged as a crucial aspect of Romania’s foreign policy. The aforementioned ties, as depicted in Table 1, function as diplomatic tools that enhance Romania’s strategic resilience and enable the pursuit of its national goals. The establishment of Strategic Partnerships represents a significant degree of cooperation, particularly with neighboring European countries, which serves to strengthen the country’s aspirations of further integration and underscore its important strategic objectives. Additionally, the capacity of Romania to engage in global issues outside its immediate geographic vicinity is exemplified by its Special and Extended Partnerships, including those established with China and India. These partnerships have facilitated collaboration across various sectors, ranging from defense to trade and energy. Hence, these Partnerships not only serve to enhance Romania’s security and stability, but also establish the nation as an engaged participant within the wider global sphere. Ultimately, the fluctuations in global geopolitics give rise to varying levels of tension, and in this context, the diplomatic engagements in question highlight Romania’s ability to adjust and its dedication to promoting cooperative approaches in addressing common difficulties.

References

Abraham, Florin. Romania since the Second World War: A Political, Social and Economic History, New York:

Bloomsbury Academic, 2016, 360 pp.

Dungaciu, Dan. Lucian Dumitrescu, “Romania’s strategic initiatives in the Black Sea area: from subregionalism

to peripheral regionalism” in Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, vol. 19, no. 2, 2019, pp. 333-351, doi:10.1080/14683857.2019.1623983.

Ge, Gao. “The Development of Sino-Romanian Relations After 1989” in Global Economic Observer: Globeco,

vol. 5, no. 1, 2017, pp. 127-136.

Ghincea, Marius. “Zeitenwende: Time for a Reassessment of Romania’s Foreign Policy?”, Bucharest: Friedrich-

Ebert-Stiftung, 2021, https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/bukarest/18580.pdf, (accessed 15 November 2023).

Joja, Iulia. “Reflections on Romania’s Role Conception in National Strategic Documents, 1990-2014: An

Evolving Security Understanding” in Europolity: Continuity and Change in European Governance, vol. 9, no. 1, 2015, pp. 89-111.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Romania, Parteneriate Strategice, (n.d.), https://mae.ro/node/1861, (accessed 15

November 2023).

―, Parteneriatul Extins cu India, (n.d.), https://mae.ro/node/35618, (accessed 17 November 2023).

―, Parteneriatul Strategic cu Regatul Spaniei, October 2023, https://mae.ro/node/21581 (accessed 14

November 2023).

―, Parteneriatul strategic cu Franța, March 2021, https://mae.ro/node/4855 (accessed 14 November 2023).

―, Parteneriatul strategic dintre România și Regatul Unit al Marii Britanii și Irlandei de Nord, March 2023,

https://mae.ro/node/55196, (accessed 14 November 2023).

―, Parteneriatul Strategic între România și Republica Azerbaidjan, (n.d.), https://mae.ro/node/5322, (accessed

14 November 2023).

―, Relația specială a României cu R. P. Chineză, March 2021, https://mae.ro/node/4852, (accessed 14

November 2023).

―, Republica Moldova, March 2021, https://mae.ro/node/1677 (accessed 14 November 2023).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, President Hu Jintao Delivers a Speech at the

Parliament of Romania, 15 June 2004, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/gjhdq_665435/3265_665445/3215_664730/3217_664734/200406/t20040615_578608.html, (accessed 17 November 2023).

―, President Hu Jintao Meets with Romanian Prime Minister Adrian Nastase, 15 June 2004,

https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/gjhdq_665435/3265_665445/3215_664730/3217_664734/200406/t20040615_578606.html (accessed 15 November 2023).

Presidential Administration of Romania, Commitments: Foreign Policy, (n.d.),

https://www.presidency.ro/en/commitments/foreign-policy, (accessed 15 November 2023).

[1] Marius Ghincea, “Zeitenwende: Time for a Reassessment of Romania’s Foreign Policy?”, Bucharest: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2021, https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/bukarest/18580.pdf, (accessed 15 November 2023).

[2] Florin Abraham, Romania since the Second World War: A Political, Social and Economic History, New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016, pp. 179-180.

[3] Ibidem, p. 179.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Florin Abraham, p. 179, op. cit.

[9] Ibidem, p. 180.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Marius Ghincea, p. 6, op. cit.

[13] Ibidem, p. 2.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid., p. 3.

[18] Ibid., pp. 2-3.

[19] Ibid., pp. 6-7.

[20] Iulia Joja, “Reflections on Romania’s Role Conception in National Strategic Documents, 1990-2014: An Evolving Security Understanding” in Europolity: Continuity and Change in European Governance, vol. 9, no. 1, 2015, pp. 89-111, cited in Ibid., p. 6.

[21] Ibid., p. 6.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Dan Dungaciu, Lucian Dumitrescu, “Romania’s strategic initiatives in the Black Sea area: from subregionalism to peripheral regionalism” in Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, vol. 19, no. 2, 2019, p. 347, doi:10.1080/14683857.2019.1623983.

[27] Marius Ghincea, op. cit., p. 3, pp. 6-7.

[28] Presidential Administration of Romania, Commitments: Foreign Policy, (n.d.), https://www.presidency.ro/en/commitments/foreign-policy, (accessed 15 November 2023).

[29] Marius Ghincea, op. cit., p. 5,

[30] Iulia Joja, op. cit., p. 107.

[31] Ibidem, pp. 107-108.

[32] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Romania, Parteneriate Strategice, (n.d.), https://mae.ro/node/1861, (accessed 15 November 2023).

[33] Presidential Administration of Romania, op. cit.

[34] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Romania, Parteneriatul Strategic cu Regatul Spaniei, October 2023, https://mae.ro/node/21581 (accessed 14 November 2023).

[35] Ibidem.

[36] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Romania, Parteneriatul Strategic între România și Republica Azerbaidjan, (n.d.), https://mae.ro/node/5322, (accessed 14 November 2023).

[37] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Romania, Parteneriatul strategic dintre România și Regatul Unit al Marii Britanii și Irlandei de Nord, March 2023, https://mae.ro/node/55196, (accessed 14 November 2023).

[38] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Romania, Parteneriatul strategic cu Franța, March 2021, https://mae.ro/node/4855 (accessed 14 November 2023).

[39] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Romania, Republica Moldova, March 2021, https://mae.ro/node/1677 (accessed 14 November 2023).

[40] Iulia Joja, op. cit., p. 108.

[41] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Romania, Relația specială a României cu R. P. Chineză, March 2021, https://mae.ro/node/4852, (accessed 14 November 2023).

[42] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, President Hu Jintao Delivers a Speech at the Parliament of Romania, 15 June 2004, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/gjhdq_665435/3265_665445/3215_664730/3217_664734/200406/t20040615_578608.html, (accessed 17 November 2023); Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, President Hu Jintao Meets with Romanian Prime Minister Adrian Nastase, 15 June 2004, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/gjhdq_665435/3265_665445/3215_664730/3217_664734/200406/t20040615_578606.html (accessed 15 November 2023).

[43] Gao Ge, “The Development of Sino-Romanian Relations After 1989” in Global Economic Observer: Globeco, vol. 5, no. 1, 2017, p. 129.

[44] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Romania, Parteneriatul Extins cu India, (n.d.), https://mae.ro/node/35618, (accessed 17 November 2023).

[45] Ibidem.