Weekly Briefing, Vol. 50. No. 3 (EE) April 2022

Like a normal schooling in the abnormal times

As discussed on a number of occasions, from 24 February 2022, Estonia has become a host-country for tens of thousands of Ukrainian war refugees. By now, there is a decent legal procedure in place, and, objectively, all the process-bound governmental bodies and institutions in Estonia are well aware of what needs to be done and how if a new refugee arrives or an existing one has a question to ask. The general mode is framed up by the Estonian society’s clear understanding that many of those war refugees are in the country to stay for a very long time, if not forever. It can only mean that Estonia is to adopt a different ‘societal look’, and it is beyond any reasonable doubts. At the same time any country’s future is primarily associated with the children’s being and their comprehension of where they are and what their country is striving for. Therefore, in the particular case of Estonia, a humongous challenge is rising up before the Government – how to seamlessly ‘accommodate’ thousands of Ukrainian children and youngsters (who arrived to Estonia either alone or, primarily, together with their mothers and/or grandparents) into the country’s educational system.

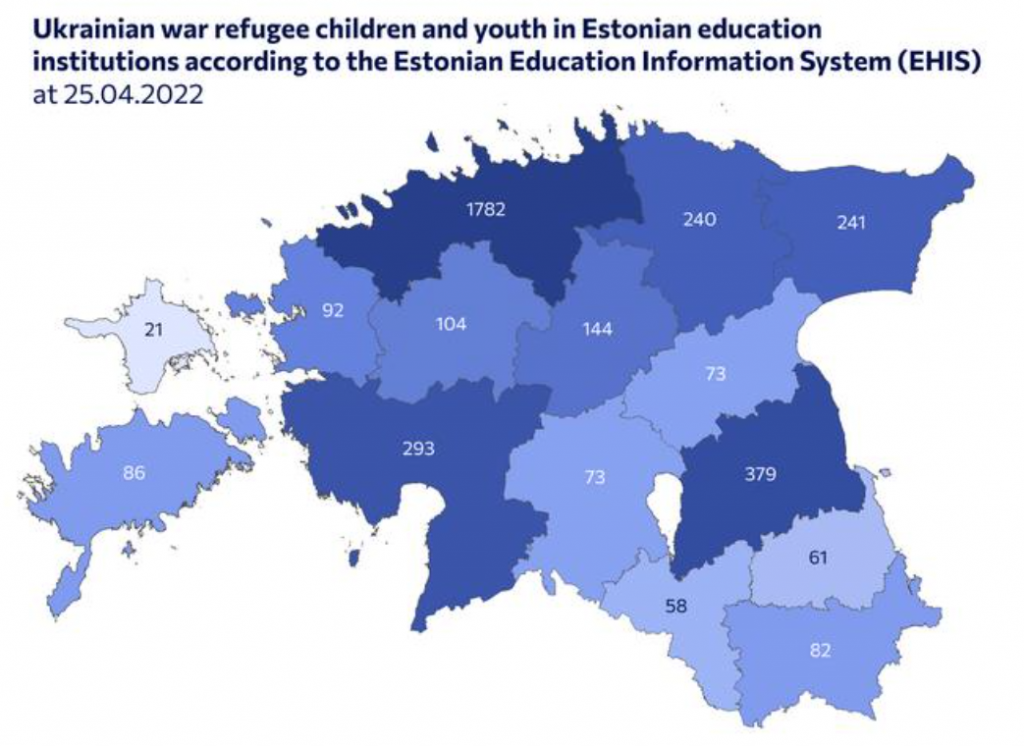

If, philosophically, everything is a number, there is a particular number in this situation as well. As reported by the Ministry of Education and Research, “[a] total of 3,206 children and young people who have arrived in Estonia from Ukraine are registered in the Estonian Education Information System […] as of 18 April”[1]. This is in addition to the fact that 80 Ukrainian war refugees have been employed as educational staff in Estonia (predominantly as teachers, teaching assistants, psychologists, and learning coordinators) by the beginning of April[2]. For the country of 1.3 million people, all these figures are already big, but they are rising every day (see Map 1 for more details).

Map 1:

Source: Ministry of Education and Research

The next step had its objective logic, – a range of schools would be required for opening up, – and the same April brought up the positive news. The country’s first Ukrainian school was opened in the capital city Tallinn, as an integral part of the already existing Lilleküla High School[3]. The inaugural ‘Ukrainian roll’ at the school was 85 children, between the ages of six and 14, and Natalja Mjalitsina, project leader, notes that all kids “are from cities that are in the news every day: Kharkiv, Mariupol, Zaporizhzhia, Kryvyi Rih, some people are from Kyiv, Mykolaiv, Odesa”, and they “don’t have a place to go”[4]. It is known that Lilleküla High School is one of the country’s leading schools in the framework of “learning by language immersion”, and this is where the whole issue becomes political since, as argued, “Estonian politicians are split on language learning for refugees”[5].

Nevertheless, it appeared that the Government as well as the vast majority of the political elites decided to leave the aforementioned prospective deliberations for the future (the next parliamentary elections are scheduled for March 2023, and the ‘Ukrainian question’ will become a major agenda-forming factor) and went ahead with announcing the establishment of a brand new educational institution, Vabaduse School in Tallinn, which is planned for providing “800 spaces for Ukrainian war refugees to continue their education in Estonia”[6]. This is going to appear to become a purpose-built school that will be “catering specifically for the needs of Ukrainian children”[7]. Projecting for a particular strategic narrative on the theme, the Vabaduse School, as reported, “will operate as a language immersion school, with principles of late immersion applied, meaning at least 60 per cent of classroom instruction will be in Estonian”[8]. Liina Kersna, the country’s Minister of Education and Research, extensively spoke on the unprecedented development:

Practically half of the war refugees in Estonia are in Harju County, with most in Tallinn, so there is a shortage of places in Estonian-language educational institutions there, so we agreed that schools in Tallinn would focus primarily on the first and second grades of general education. […] The building on Endla tänav is in the city centre, making it much more accessible than the [previous choice].[9]

Considering the undisputed fact that the Russo-Ukrainian War is far from being over, there will be, speculatively, some other similar announcements and developments – based on the current status quo, numbers wise, there can be more than 2,000 children from Ukraine who prospectively can be registered in the Estonian Education Information System by the end of 2022. These astonishing numbers are, with necessity, to push for a range of tectonic changes in Estonia’s educational sphere, bringing up myriads of socio-political and politico-economic questions in need for answering by professionals. For example, as reported, the same Vabaduse School, which managed to enrol 500 students by the middle of summer, is still lacking about 60 staff members[10]. In the meantime, the process of integrating the Ukrainian children into the Estonian society is under way. For the upcoming summer, there is a plan to arrange a few integration and language learning camps for both Estonian and Ukrainian children across the country, engaging several localities and take some pressure off Tallinn. As noted, “more than 11,000 young people will be able to participate in the camps”[11].

Given the level of expenses that Estonia (and many other Member States of the EU) is incurring as a host-country for Ukrainian war refugees, it is interesting to discover that the EU’s contribution to Estonia to assist the country in covering the unexpected financial burden has been EUR 9 million to the end of May[12]. It was reported that the European Commission has already allocated a total of EUR 400 million to be “available for migration and border management in its member states through the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF) and the Border Management and Visa Instrument”[13]. In details, however, the lion share of the aforementioned funding have been ‘heading’ predominantly to the countries, which have borders with Ukraine (Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia), with an addition of the Czech Republic – these Member States of the EU have received about EUR 250 million[14]. The remaining EUR 150 odd million have been allocated for the rest, thus Estonia has ended up with such a marginal help, which, as specified, is “not intended to be used for the long-term support of refugees”[15].

Arguably, across the EU, the upcoming September-October when the new year’s budgets are going to appear in their first draft versions, there will be plenty of new items, which will be addressing the Ukrainian war refugees-associated social issues. The political elites in the Baltic states are already calling “for additional funds from the EU for countries where the number of Ukrainian refugees seeking protection has exceeded 1 per cent of the population”[16]. This is indeed the case for all of the three Baltics, because, by the middle of June, “[m]ore than 50,000 Ukrainian refugees have applied for temporary protection in Lithuania, over 43,000 in Estonia and over 26,000 in Latvia”[17], proving the 1 per cent claim. With those figures to be perpetually increasing in the foreseeable future, a higher number of Ukrainian children will get settled in Estonia. Certainly, for them, everything can look like a normal schooling at a welcoming foreign country and with an addition of an interesting foreign language to learn. For the adults in the Government, it will be a conceptually different range of learning curves and challenges to face – in general, this is the situation, which no previous Estonian Government have ever experienced.

[1] ‘More than three thousand children who fled the war in Ukraine are registered in Estonian educational institutions’ in the Ministry of Education and Research of the Republic of Estonia, 19 April 2022. Available from [https://www.hm.ee/en/news/more-three-thousand-children-who-fled-war-ukraine-are-registered-estonian-educational].

[2] ‘More than three thousand children who fled the war in Ukraine are registered in Estonian educational institutions’.

[3] ‘Ukrainian school in Tallinn: We’re like a normal school’ in ERR, 27 April 2022. Available from [https://news.err.ee/1608577639/feature-ukrainian-school-in-tallinn-we-re-like-a-normal-school].

[4] Natalja Mjalitsina as cited in ‘Ukrainian school in Tallinn: We’re like a normal school’

[5] ‘Ukrainian school in Tallinn: We’re like a normal school’.

[6] ‘School for 800 Ukrainian children set to open in Tallinn’ in ERR, 26 May 2022. Available from [https://news.err.ee/1608609358/school-for-800-ukrainian-children-set-to-open-in-tallinn].

[7] ‘School for 800 Ukrainian children set to open in Tallinn’.

[8] ‘School for 800 Ukrainian children set to open in Tallinn’.

[9] Liina Kersna as cited in ‘School for 800 Ukrainian children set to open in Tallinn’.

[10] ‘Ukrainian school preparing for academic year, still short on teachers’ in ERR, 25 July 2022. Available from [https://news.err.ee/1608666397/ukrainian-school-preparing-for-academic-year-still-short-on-teachers].

[11] ‘Summer integration camps begin for 11,000 Ukrainian and Estonian children’ in ERR, 5 July 2022. Available from [https://news.err.ee/1608648136/summer-integration-camps-begin-for-11-000-ukrainian-and-estonian-children].

[12] ‘EU funding for Ukraine war refugees in Estonia remains marginal’ in ERR, 11 July 2022. Available from [https://news.err.ee/1608654079/eu-funding-for-ukraine-war-refugees-in-estonia-remains-marginal].

[13] ‘EU funding for Ukraine war refugees in Estonia remains marginal’.

[14] ‘EU funding for Ukraine war refugees in Estonia remains marginal’.

[15] ‘EU funding for Ukraine war refugees in Estonia remains marginal’.

[16] ‘Baltic leaders: Help needed for countries hosting Ukrainian refugees’ in ERR, 21 June 2022. Available from [https://news.err.ee/1608636208/baltic-leaders-help-needed-for-countries-hosting-ukrainian-refugees].

[17] ‘Baltic leaders: Help needed for countries hosting Ukrainian refugees’.