Weekly Briefing, Vol. 33. No. 4 (EE) October 2020

The geo-strategic arithmetic of the Three Seas Initiative

Apart from the other ground-breaking events, the end of the XVIII century was featured by the disappearance of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from the world’s political map. Having enjoyed the status of one of the world’s largest countries for more than 200 years, the Commonwealth was powerful enough to somewhat unify many European peoples, while also interlinking the Baltic and Black Seas. The global turbulences, which were associated with the entity’s final century, did not allow the Polish–Lithuanian state to live on because some of its neighbours (Russia, Prussia, and Austria) had a diametrically different opinion on the matter. During the course of the WWI, Poland, the core element of the late Commonwealth, together with Lithuania, managed to re-appear politically. Just as well, the post-WWI map of Europe had been under substantial redesign, due to the subsequent collapses of Russia, German, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman empires. Romania adopted its largest ever geographical form, Estonia and Latvia – for the first time – enjoyed successes of international recognition as independent states, Czechoslovakia commenced its existence in the heart of Europe, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes started dominating in the Balkans, and the first statehoods of Belarus and Ukraine ended up to be among the titular members of the newly formed Soviet Union.

That was when Józef Piłsudski, the First Marshall of Poland, attempted to establish a quasi-federative entity that would be making a geo-strategic interlinkage between Finland, the Baltics, Romania, and the Balkans via Poland as well as interconnectedness of the Black, Baltic and Adriatic Seas. Ultimately, the whole idea – known as Międzymorze or Intermarium – was to weaken the USSR, but the leading role of/for Poland was never hidden when the concept was getting discussed. In 1939, the interwar period dramatically ended on the fronts of the WWII, and Intermarium had been forgotten until 2005. The Orange Revolution brought the ‘Ukrainian question’ back to the surface of global politics, and the Central-Eastern region of Europe got some excitement from attempting to produce yet another geo-strategically relevant example of neo-regionalism. In December 2005, in Kyiv, nine European countries (Estonia, the then FYR Macedonia, Georgia, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Romania, Slovenia and Ukraine) gave it a good go and created the Community of Democratic Choice[1]. The third sea in this exercise was visualised to be Caspian, via Azerbaijan having become one of the observers of the grouping. Within a couple of years since its inception, it became clear that the Community failed to deliver, quietly proceeding into the irrelevance. The region had to wait for April 2012 when Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao arrived in Warsaw to revitalise the matter in principle[2], even though nothing on Intermarium or similar historic ideas had ever been pronounced. On the one side, the situation looked quite normal – sending ‘greetings’ to Marshall Piłsudski ‘back to the future’, Poland was indirectly recognised as the core element of the newly proposed 16+1 framework. On the other side, there was something that seemed to be very extravagant – for the first time in modern history, a major Asian power had been designating a region in Europe to cooperate with. In a year, the situation became much clearer when the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was announced, and the 16+1 framework, under the skilful guidance of Prime Minister Li Keqiang, became treated in different European capitals as an integral part of the main Initiative. In a way, for the Europeans, it would be a big strategic misconception to treat the 16+1 as a something that would have nothing to do with the BRI.

One does not need to be an expert in the field of international relations to recognise the presence of the EU in the European continent, presuming that the EU could have its own vision on how the process of pan-continental integration would need to be framed up. For example, no later than on 23 September 2020, the European Commission adopted the already third report on the implementation of the four EU macro-regional strategies: the EU Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region, the EU Strategy for the Danube Region, the EU Strategy for the Adriatic and Ionian Region, and the EU Strategy for the Alpine Region[3] (see their logos in Picture 1). Clearly, these geo-strategic dimensions represent a number of parallel vectors, while the 16+1 (that is now known as 17+1, since Greece joined it in 2019), go across those vectors, in a perpendicular way. Should this situation be of a serious concern for the EU (for instance, due to an obvious prospect of its segmentation), the entity could directly talk to China in order to clarify the status quo.

Picture 1: The EU’s macro-regional strategies

Source: The European Commission

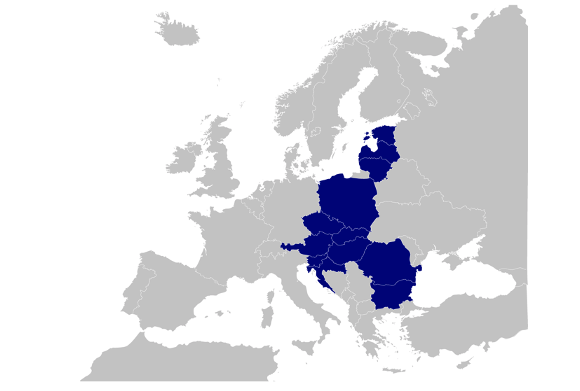

Has the EU managed to deliver its massage to the Chinese side? Yes, it has, but definitely not in a timely manner and not always directly. The first more or less serious direct ‘conversation’ that the EU initiated on the then 16+1 was framed up as a European Parliament’s resolution of 12 September 2018, more than six years (!!!) after the commencement of the China-initiated framework. In the resolution, the 16+1 was acknowledged in the context of the EU-China relations[4], and China quickly responded with its ‘Policy Paper on the European Union’[5]. Arguably, the communication had begun. At the same time, there was something that could be considered an indirect response to the 16+1. In 2015, during the UN General Assembly, the President of Croatia Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović and the President of Poland Andrzej Duda discussed the idea on developing the Three Seas Initiative (3SI, see Picture 2), sending yet another lot of ‘regards’ to Józef Piłsudski and paving the way for the framework to hold its first summit in Dubrovnik, in 2016[6]. This is where the common knowledge of history should stop exhibiting different facts, leaving the ‘room’ for political science to construct a proper discussional framework.

Picture 2: The Three Seas Initiative

Source: 3seas.eu

In principle, the 3SI makes perfect sense since, as declared, it is aiming at designing a framework “to accelerate the development of energy, transport and digital infrastructure in order to increase the region’s economic growth, reinforce its economic resilience and further the vision of an integrated, cohesive and undivided Europe”[7]. In addition to all sorts of historical connotations, the 3SI is monogenous, – all members of the framework are EU Member States, – and this factor can ensure a certain degree of its operational capacity for future institutionalisation and other developments. At the same time, whatever the name is chosen to call the idea by, in the field of political science the 3SI is to be treated as a mechanism to counterbalance the BRI (and the 17+1 as its integral element). Evidently, the ‘conversation’ between the EU and China on the matter has not brought up any fruitful results – firstly, the COVID-19 crisis made it impossible for the two sides to continue normal discussions on a post-2020 strategic partnership-associated document, and, secondly, as argued, some of the Central-Eastern European counties “had already begun socially distancing from Beijing and the coronavirus pandemic has only accelerated this process”[8].

On 19 October 19, the 3SI’s virtual forum took place in Estonia. In a significant addition, the board of the 3SI Investment Fund made an announcement that Estonia decided to join it as core investor, investing “up to EUR 20 million into the Fund”[9]. Martin Helme, the country’s Minister of Finance, noted that “[t]he cooperation of Three Seas countries is important for us, therefore we also want to contribute to the joint fund and soon hope to see the first investments”[10]. In academic terms, this can only mean that the situation is at a point when the 17+1 vs. 3SI inevitable clash can either represent a monumental opportunity for the EU and China to positively cooperate in year to come or a possibility for the two sides to be in an ever-expanding permanent geo-strategic conflict over the issue. The next two years will clarify plenty on the aforementioned dilemma.

[1] Vlad Vernygora and Natalia Chaban, ‘New Europe and its neo-regionalism: the working case of the Community of Democratic Choice’ in TRAMES (Tallinn: Estonian Academy Publishers), Vol. 12, issue 2, 2008, pp. 127-150.

[2] ‘Premier Wen Jiabao leaves for home after visit to Poland’ in Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the People’s Republic of China, 28 April 2012. Available from [https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/wjbispg_665714/t928040.shtml].

[3] ‘The Commission adopts the third report on the implementation of EU macro-regional strategies’ in the European Commission, 24 September 2020. Available from [https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/newsroom/news/2020/09/24-09-2020-the-commission-adopts-the-third-report-on-the-implementation-of-eu-macro-regional-strategies].

[4] ‘European Parliament resolution of 12 September 2018 on the state of EU-China relations’ in the European Parliament, 12 September 2020. Available from [https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2018-0343_EN.html].

[5] ‘Full text of China’s Policy Paper on the European Union’ in Xinhua, 18 December 2018. Available from [http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-12/18/c_137681829.htm].

[6] ‘Three Seas Initiative (3SI)’ in Välisministeerium. Available from [https://vm.ee/en/three-seas-initiative-3si#History].

[7] ‘Secretariat of the Three Seas created’ in 3seas.eu. Available from [https://www.3seas.eu/media/news/secretariat-of-the-three-seas-was-created]. Emphasis is ours.

[8] Emilian Kavalski, ‘How China lost central and eastern Europe’ in The Conversation, 27 July 2020. Available from [https://theconversation.com/how-china-lost-central-and-eastern-europe-142416].

[9] ‘Estonia joined the Three Seas Initiative Investment Fund’ in 3seas.eu. Available from [https://www.3seas.eu/media/news/estonia-joined-the-three-seas-initiative-investment-fund].

[10] Martin Helme as cited in ‘Estonia joined the Three Seas Initiative Investment Fund’.