Weekly Briefing, Vol. 37, No. 3 (BG), February 2021

The Changes in Bulgarian Social Strata in the Past 30 Years

In the last 30 years, two global processes had an impact on Bulgaria. In the first place, this was the transition from advanced socialism to liberal capitalism as a model, structure and functioning of society. Secondly, the over-monopolization of the world economy and the over-concentration of world politics naturally led to the over-polarization and oligarchization of social stratification in global society. Thus the transition (1989–2007) and the years after that changed the system of society in Bulgaria. The transformations were not only extremely fast and shocking for the vast part of the Bulgarian nation, but also comprehensive – in all spheres of society, in the way it functions, in its institutions, norms and morals, in the global positioning of Bulgaria. In essence, the structural-functional model of society was changed – from “socialist” it became “capitalist”. Although the new society in Bulgaria is usually described as: “democratic, market, open, free, Euro-Atlantic and multicultural”, in reality, the most accurate characteristic is an “extremely liberal capitalist” society. As a result a natural process of accelerated and painful social differentiation has developed. Many additional dividing lines were formed, acting not in the direction of integration into society, but of its disintegration. These are new social dividing lines caused by a combination of extremely powerful factors and processes.

All this led to a sharp complication of the social hierarchy of social inequalities. In addition, the top and bottom of the social pyramid were painfully far apart. The middle class literally melted away, became impoverished and was declassified, thus losing its social resilience. The low class of poor routine and unskilled labor began to disintegrate into an integrated stratum against communities that fall into apathy and discouraged unemployment, helpless and at the risk of lumpenization. The mass of outsider communities was growing sharply, developing its network of gray areas in social institutions, entire villages and municipalities in the country. In general, the stratification profile of the population in Bulgaria degraded from a profile typical of Central and Southern Europe from the 1980s to the profile that was then typical of Latin American countries, and is now a profile of the United States.

In summary, the social differentiation in the last 30 years in Bulgaria has developed towards increasing and deepening the differences – to a degree of disintegration. Practical evidence of the growing process of social disintegration and anomie are both the depopulation of huge areas in the country and the overcrowding of other areas with degraded populations.

At the beginning of the transition in Bulgarian society, there was a hope that the stratification profile of the “middle class society” that Bulgaria had in the mid-1980s will be preserved. In reality, however, the exact opposite happened. The new elites quickly usurped real power and public policy. They were created in the 1990s primarily through the new private banking system and privatization process. The structural result of the emergence of the new capital class in Bulgaria led to the formation of an oligarchic peak in the social pyramid. As a result of the changes in the Bulgarian society in the 1990s, two social poles were formed – of super-wealth as a peak that broke away from society and of super-poverty excluded under society, which expanded into a huge mass and sank more and more below the bottom of society in misery and isolation. We are talking about 20-30 oligarchic plus several thousand close families at the top of the pyramid against 20-25% (over 1.5 million people) in full misery and illiteracy, helplessness, degradation and social exclusion. Thus, two specific group and community interests were formed. They separate and oppose not only each other, but also society as a whole. At the bottom of the pyramid, against the new elites, isolated ghetto communities formed. Between these two social poles, the upper middle class remained relatively stable. This was to the extent that public institutions, businesses and corporations, politics and the media in Bulgaria need the expertise and services of specialists.

The tragedy is in the middle class of the middle class – there is a sharp contraction and crushing of business, the intelligentsia, the middle management. The lower middle class was also being crushed. A huge part of it fallen down to poverty and insecurity which led to declassification.

Beneath it the lower strata of relative poverty, of the modern proletariat (workers’, farmers’, merchants’, bureaucrats, artisans) are expanding. Unemployment, illiteracy, and lumpenization are becoming widespread. This is a direct consequence of low wages and miserable pensions, of miserable family and maternal support. It is extremely important that in this floor of the social pyramid a very negative process of meaninglessness of labor as a value develops. This undermines the model of realization through work, the idea of a better life status through work. The “depth of poverty” indicator is increasing. Most people become unemployed, permanently unemployed and discouraged. Thus, they lose their human capital, some begin to lumpenize, lose their integrity to the nation, and became aggressive towards their country. Modern social analysts call this class a precariat. A typical example of precariat in Bulgaria are the so-called “working poor”, i.e. people who work but still keep their incomes on the social bottom. But not only they are part of the Bulgarian precariat, ie. the layer of declassified and deprofessionalized personalities. Trapped in the labyrinth of poverty, insecurity, unsustainability of their labor integration, young and not so young Bulgarians become passive individuals, avoid any social responsibility, do not create families and do not want to have children. Through the years not a small part of this population decided to immigrate to abroad.

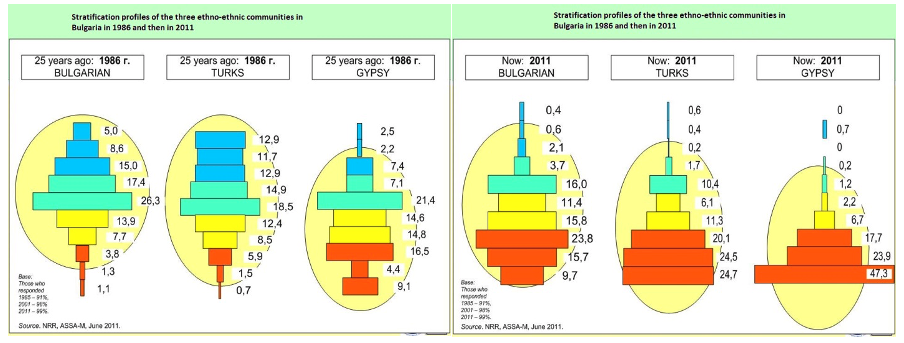

A survey conducted by the Bulgarian sociological agency ASSA-M several years ago clearly shows the dynamics of the sociological profiles of the three ethno-ethnic communities in Bulgaria in 1986 and then in 2011 as a result of Globalization and Transition. The drastic contraction and decline of the middle class can be seen. It becomes such a small percentage in the general structure of the population that it creates visibility for lack. The other stressful problem is that a large part of the remaining lower middle class (people with small and weak businesses, impoverished intelligentsia and employees, technology workers, craftsmen, small services – utilities, education and health, social and information) nominally still have the position of the middle class, but with great fear for the future, in the face of a direct threat of declassification, of falling into poverty. The perspective is cut off, and this is fatal for the self-confidence of the middle class. The socialized low levels below the middle class (the modern “working class”, the so-called “relative poverty” layer) first increase because they accept a large part of the previous middle class, but then fall down to deep poverty and some to misery, exclusion and becoming social outsiders.

Source: ASSA-M, June 2011

All this is not just social downgrading and depression. This is a powerful process of removing from the labor force of the economy and the state a huge part of the productive low-status professions and occupations. This is a serious social problem for downgraded people and families. It is also a social barrier to modernizing the economy and increasing the efficiency of all public institutions.

The data show that Bulgaria is among the countries where young people experience the most serious difficulties in their realization on the labor market. The employment rate among young people in the country remains at extremely low levels (20%), far from the EU average (nearly 34 %). In fact, only 4 countries can “boast” lower employment. If we look at the unemployment rate, we will see that Bulgaria is above the average levels in the EU, although the country is further away from the leaders in this indicator.

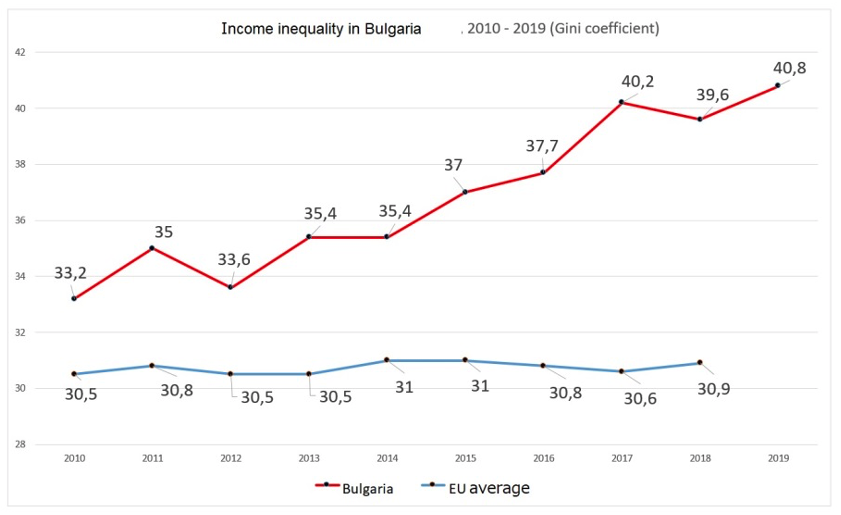

Bulgaria set a new record in terms of economic inequality in the country, as in 2019 it registered a Gini coefficient of 40.8. This is the highest level, at least since the Second World War that Bulgaria reaches in the international index, which is used as a statistical characteristic of the distribution of wealth in a society and measures the difference between the welfare of the poor and rich in it. The graphics below shows exactly how much Bulgaria deviates from the European average, which varies at a significantly lower level – around a coefficient of 30 – 31.

Source: Eurostat

The data from the other measure of inequality – the so-called quintile income distribution in European societies or the difference between the richest 20% and the poorest 20% in individual countries is also very clear. According to this indicator, Bulgaria notes an increase in inequality – if in 2018 the difference was 7.66 times, in 2019 it is already 8.10 times.

The problem of inequality in Bulgaria does not go unnoticed by the European Commission, which for years in its reports defines the situation on this indicator in our country as “critical”. The combination of economic growth and high levels of inequality means that newly created wealth is concentrated at the top of the income chain. The data show that more than half of Bulgarians (53.8%) earn up to BGN 500 (250 EUR) per month, and nearly 80% – up to BGN 900 (450 EUR), without including another 2 million pensioners with an average pension of about 370 BGN (186 EUR). At the same time, only 1% of the people in Bulgaria earn more than BGN 6,000 (3000 EUR) per month, and in this narrowest group at the top of the pyramid the inequality is even greater.

Source: Bulgarian National Income Agency

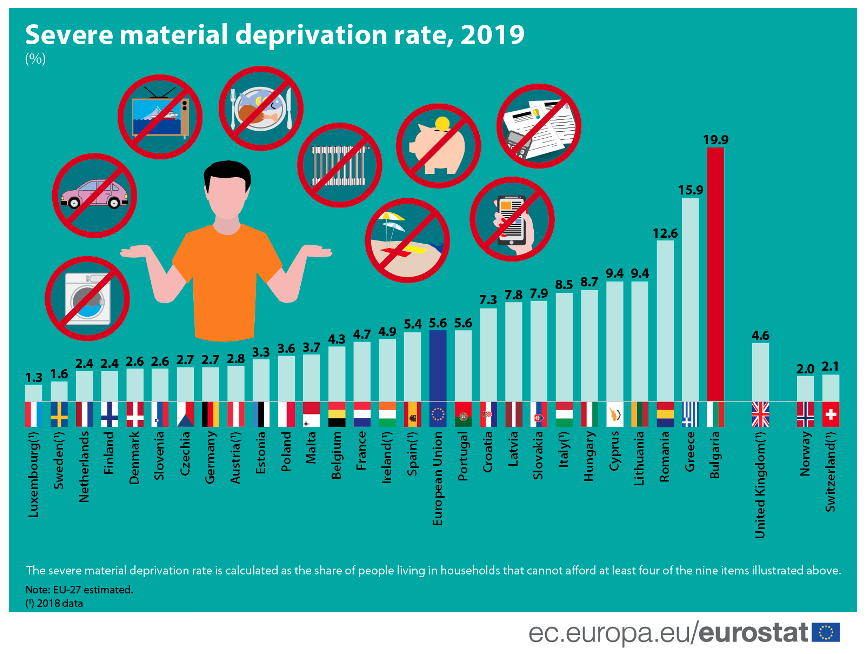

The picture is even worse when we take into account that Across the EU Member States, Bulgaria (19.9%) registered the highest shares of severe material deprivation in 2019. The term was introduced to summarize the percentage of people who cannot afford at least four of the few “conveniences” that are considered signs of a normal life: paying bills on time; keeping the home adequately warm; the way they deal with unexpected expenses; eating meat, fish or a vegetarian equivalent on a regular basis; possibility for a week’s vacation away from home, as well as possession of a TV, washing machine, car and telephone. The data clearly shows that every fifth Bulgarian faces such severe material deprivation.

In conclusion, in the last thirty years Bulgarian society has reached a rapid process of fragmentation. The individual floors in the social pyramid shrink their subjective social horizon to the scope of their individual life and reference groups, to the micro-communities with specific problems. The values of collective egoism dominate, which is becoming more and more aggressive. This is inevitable in a social environment in which situations of survival prevail, instead of work and prosperity, instead of social integration and reliance on law and order, care and support from the state.